Last Updated: 9/11/2025 | 22 min. read

Investing in the crypto asset class means investing in blockchain technology: computer networks running open-source software to maintain a public database of transactions. This technology is transforming the way things of value — money and assets — move on the internet. Grayscale believes that blockchains will revolutionize digital commerce, with wide-ranging implications for our payment systems and capital markets infrastructure.

But the value of this technology — the utility it offers to users — is not just about efficiency gains in financial intermediation. Bitcoin and Ethereum are both payment systems and monetary assets.[1] These cryptocurrencies have certain design features that can make them a refuge, when needed, from conventional fiat money. To understand how blockchains work, you need to understand computer science and cryptography. But to understand why crypto assets have value, you need tounderstand fiat currencies and macroeconomic imbalances.

Virtually all modern economies use a fiat money system: paper currency (and its digital representations) with no intrinsic value. It can be surprising to realize that most of the world’s wealth has at its foundation a worthless physical object. But, of course, fiat money is not really about the paper currency itself but the institutions that surround it.

For these systems to work, expectations about the supply of the currency need to be anchored in something — no one would use paper currency if there were no commitment whatsoever to limit the supply. Therefore, governments make promises not to excessively increase the supply of money, and the public makes a judgment about the credibility of those promises. It is a system based on trust.

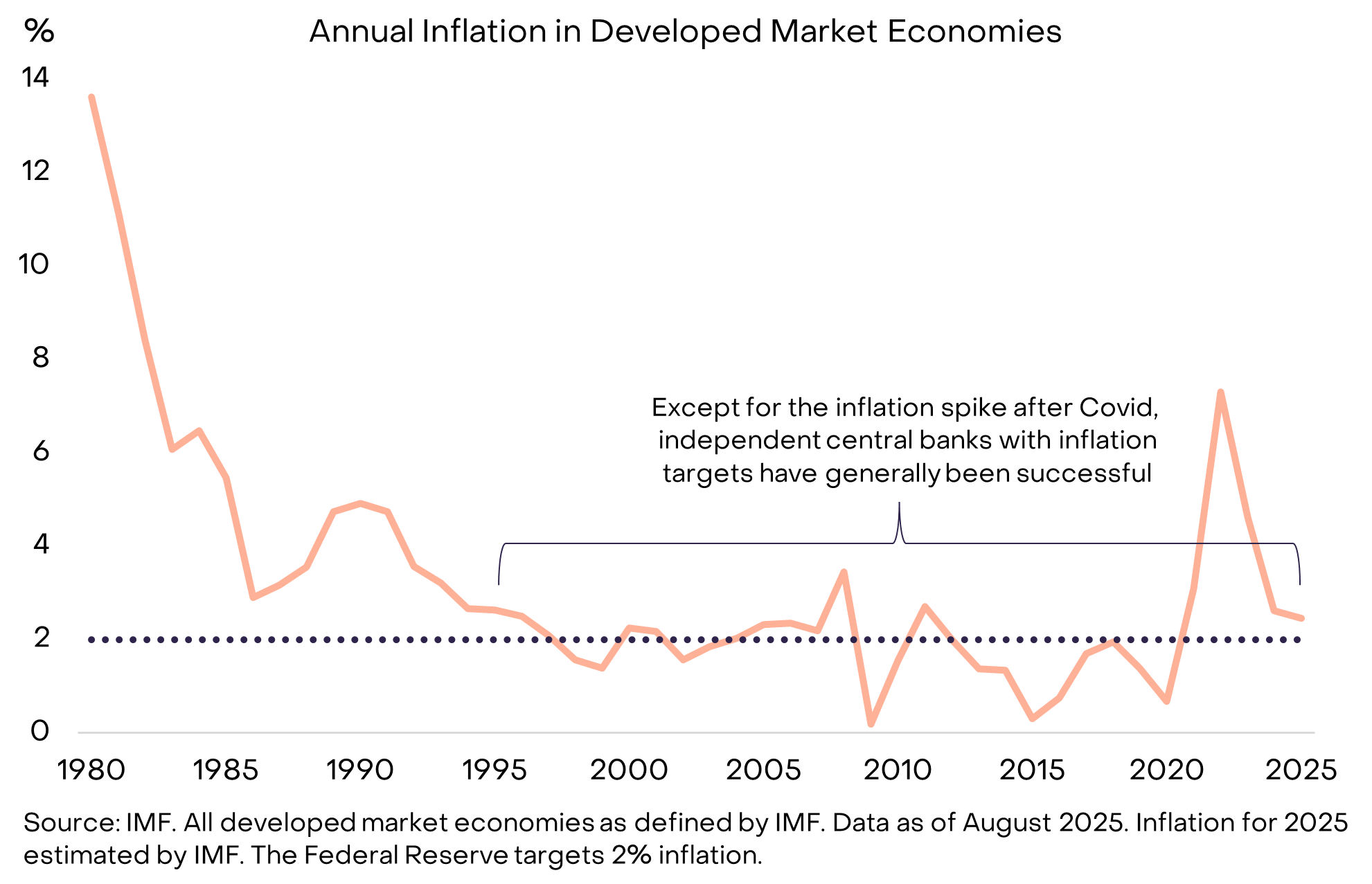

However, history is replete with examples of governments violating that trust: policymakers sometimes increase the money supply (causing inflation) because it is the expedient option at the time. Therefore, holders of money are naturally skeptical of generic promises about limiting the supply of fiat money. To make the commitment more credible, governments typically employ some kind of institutional framework. These differ over time and across countries, but the most common strategy today is to delegate responsibility for managing the money supply to an independent central bank, which in turn articulates a specific target for inflation. This structure, which has been the norm since roughly the mid-1990s, has largely been effective at delivering low inflation (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Inflation targeting and central bank independence help build trust

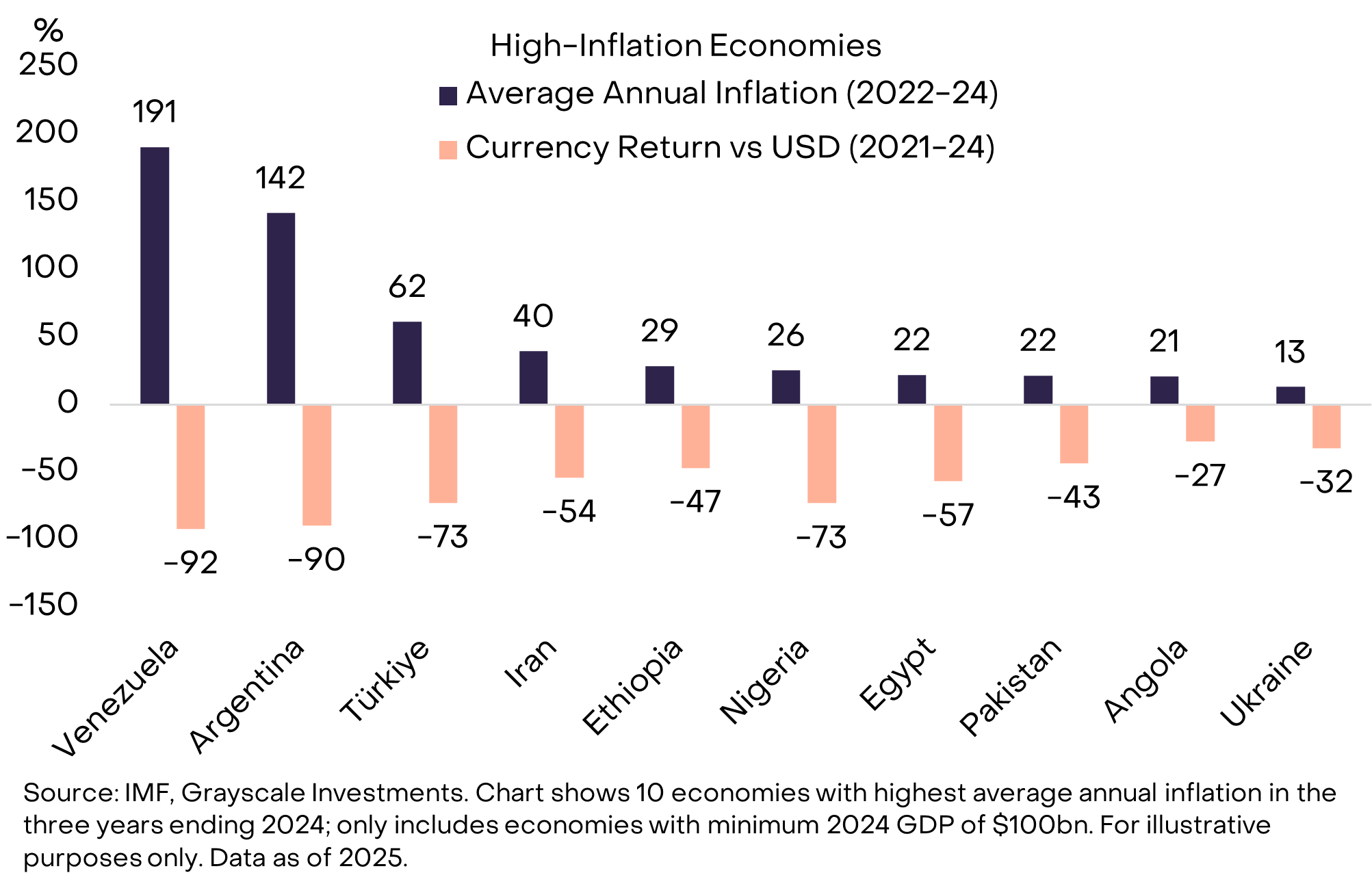

When fiat currency is highly credible, the public doesn’t pay the issue any mind. That is the goal.[2] And for citizens in countries with a history of low and stable inflation, the point of holding a currency that can’t be used for day-to-day payments or to settle debts can be hard to grasp. But there are many places around the world where the need for better money is obvious (Exhibit 2). No one questions why the citizens of Venezuela or Argentina would want to hold a portion of their assets in a foreign currencies or certain crypto assets — they very clearly need a better store of value.

Exhibit 2: Governments occasionally mismanage the money supply

The 10 countries in the chart above have a combined population of about 1 billion people, and many of them have used crypto as a monetary life raft. This includes Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, but also the Tether (USDT) stablecoin, which is a blockchain-based asset tied to the U.S. Dollar. Adoption of Tether and other stablecoins is just another form of Dollarization — substitution out of the domestic fiat currency into U.S. Dollars — which has been common in emerging markets for decades.

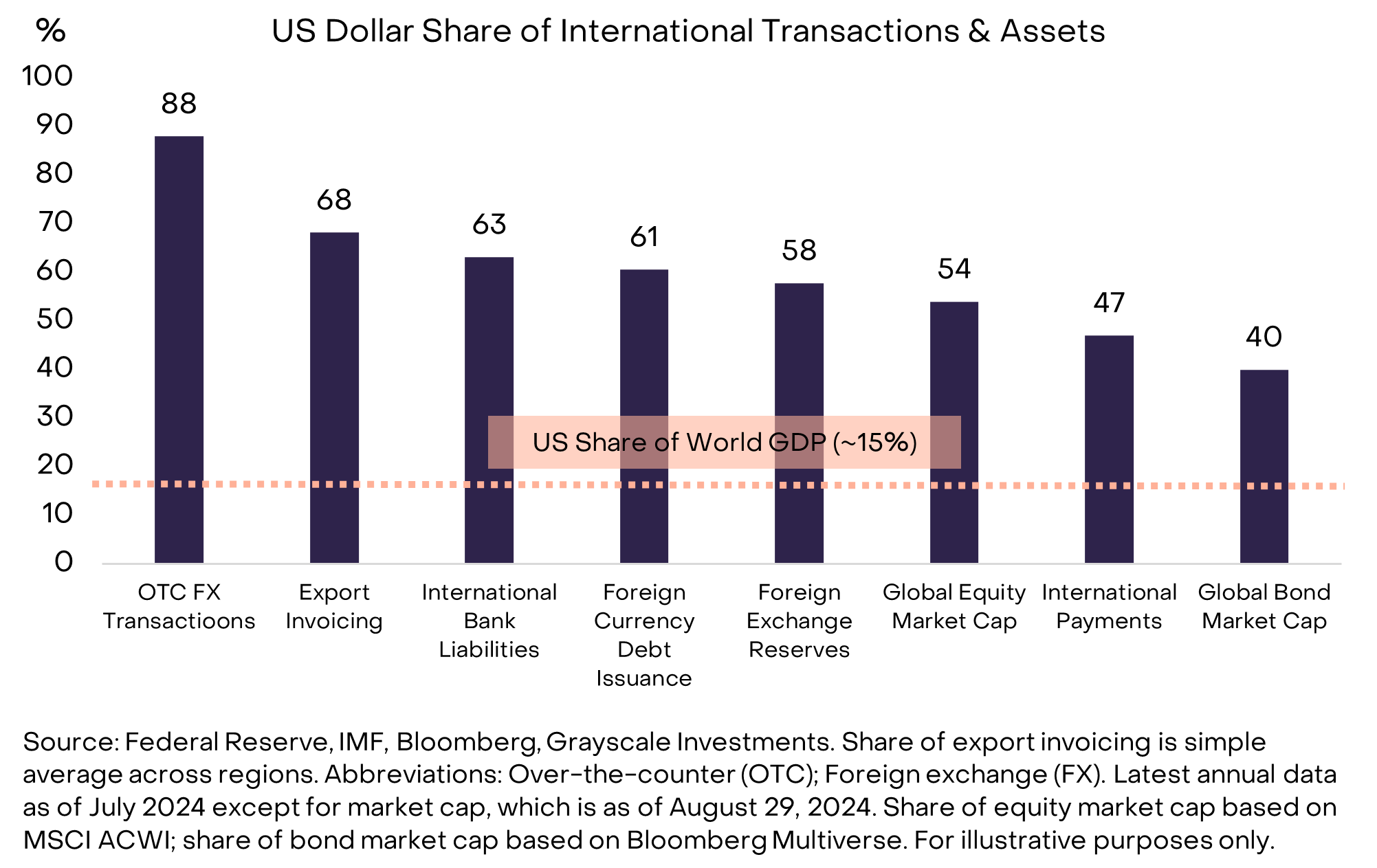

But what if the problem is the Dollar itself? If you are a multinational corporation, a high-net-worth individual, or a nation state, there is no escaping the U.S. Dollar. The Dollar is both the domestic currency of the United States and the dominant international currency in the world today. Aggregating over a variety of specific indicators, the Federal Reserve estimates that the U.S. Dollar accounts for about 60%-70% of international currency usage, compared to just 20%-25% for the Euro and less than 5% for the Chinese Renminbi (Exhibit 3).[3]

Exhibit 3: U.S. Dollar is the dominant international currency today

To be clear, the United States does not have a problem with monetary mismanagement comparable to the emerging-market economies in Exhibit 2. However, any threat to the soundness of the U.S. Dollar matters because it affects nearly all asset holders — not just U.S. residents that use the Dollar for everyday transactions. Risks to the Dollar, rather than the Argentine Peso or Venezuelan Bolivar, are what drive the largest pools of capital to seek out alternatives like gold and cryptocurrencies. Compared to other countries, the potential challenges with monetary stability in the U.S. may not be the most severe, but they are the most important.

Fiat currencies are based on promises, trust, and credibility. In our view, the Dollar faces an emerging credibility problem, in that it is becoming harder for the U.S. government to make a believable commitment to low inflation over time. The root cause of this credibility gap relates to unsustainable federal government deficits and debt.

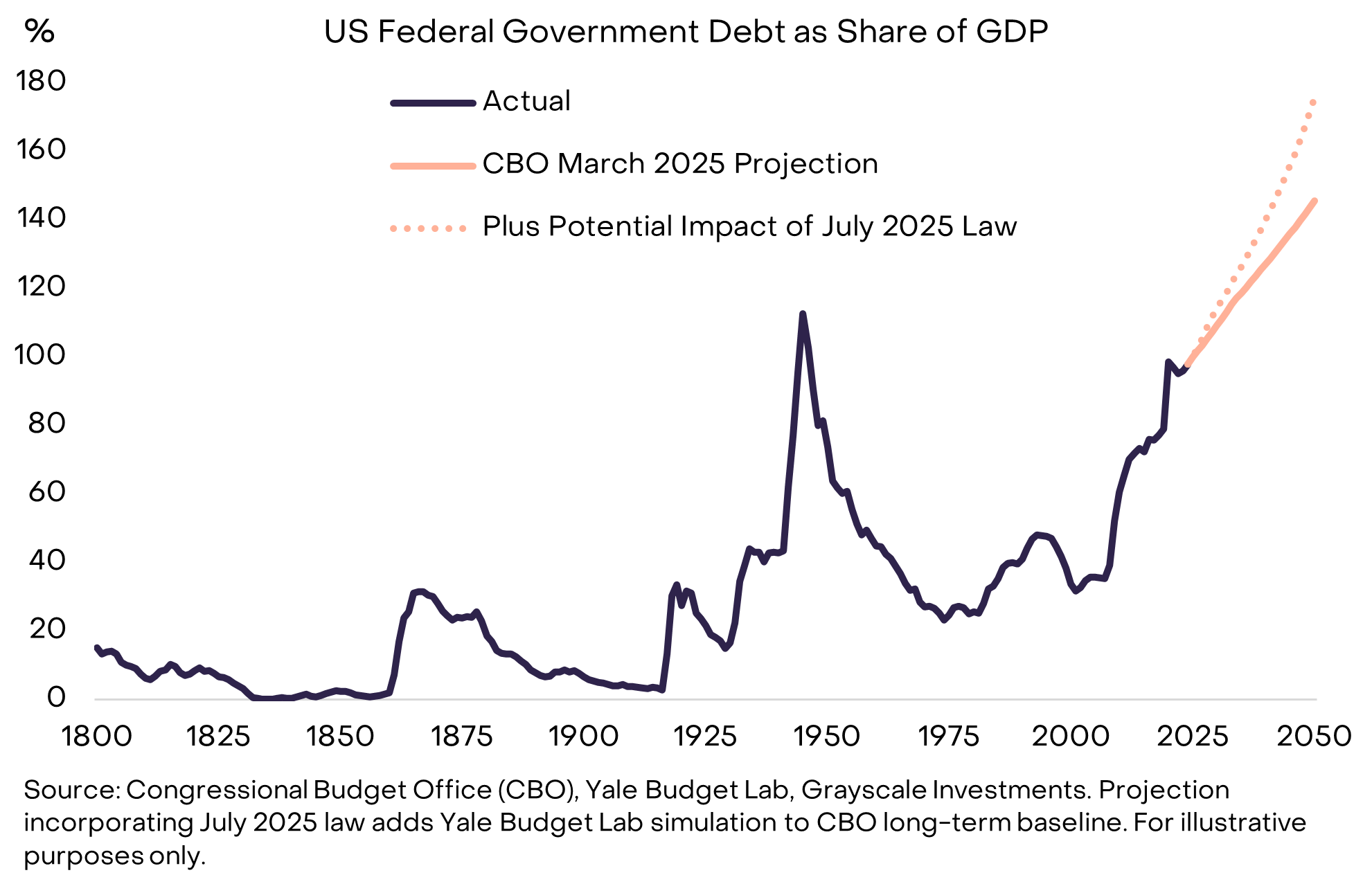

The imbalances started to build with the 2008 financial crisis. In 2007, the U.S. had a deficit of just 1% of GDP and a debt stock of 35% of GDP. Since that time, the federal government has run an average annual deficit of about 6% of GDP.[4] The national debt is now about $30 trillion or roughly 100% of GDP — almost as much as the final year of WWII — and is expected to remain on a sharply increasing trajectory (Exhibit 4).[5]

Exhibit 4: U.S. public debt on an unsustainable path higher

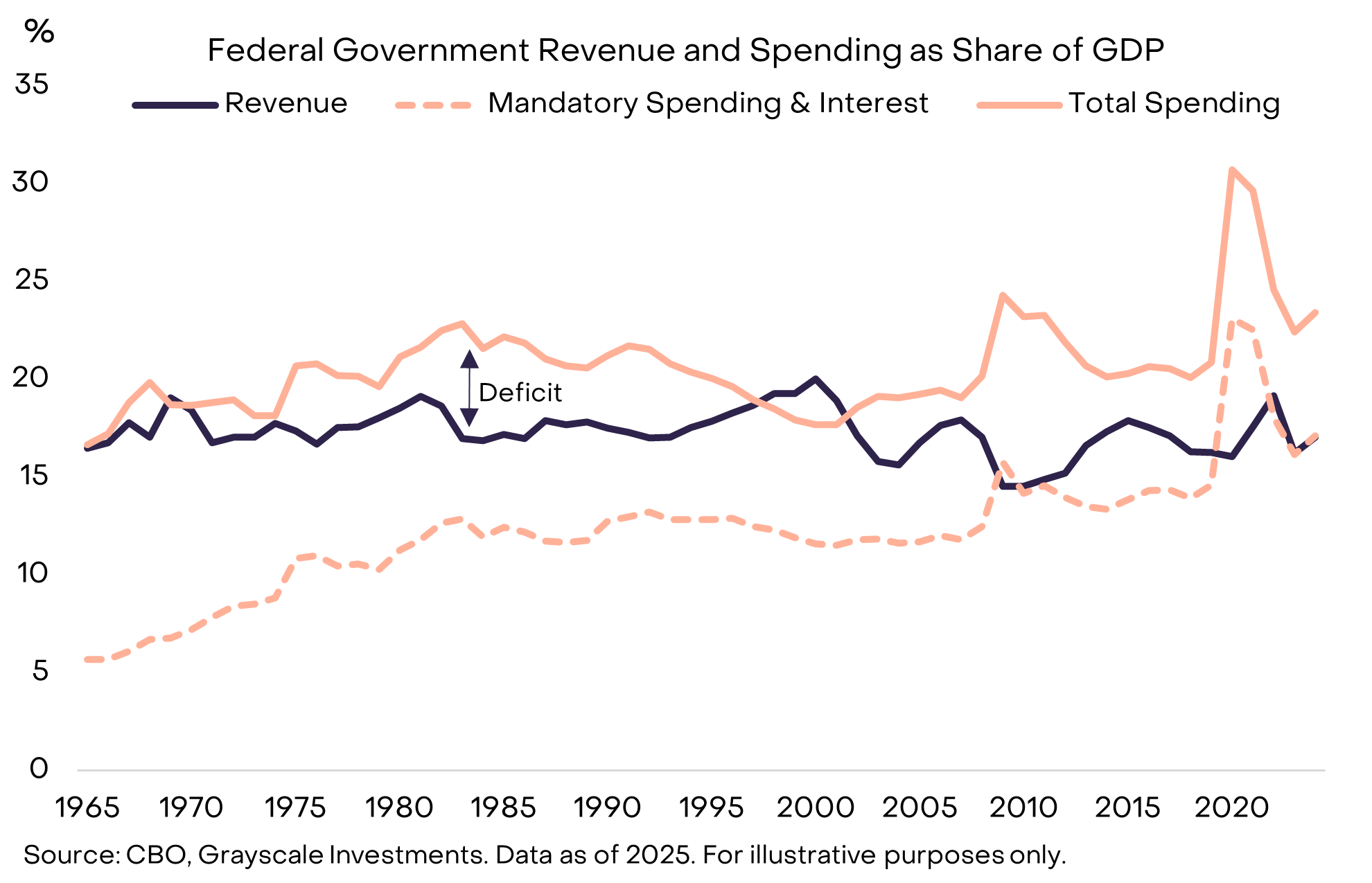

Large deficits have been a bipartisan issue and have been sustained even when the unemployment rate was relatively low. One reason modern deficits seem intractable is that revenues now only cover mandatory spending (programs like Social Security and Medicare) and interest payments (Exhibit 5). Therefore, balancing the budget may require politically painful spending cuts and/or higher taxes.

Exhibit 5: Government revenues only cover mandatory spending plus interest

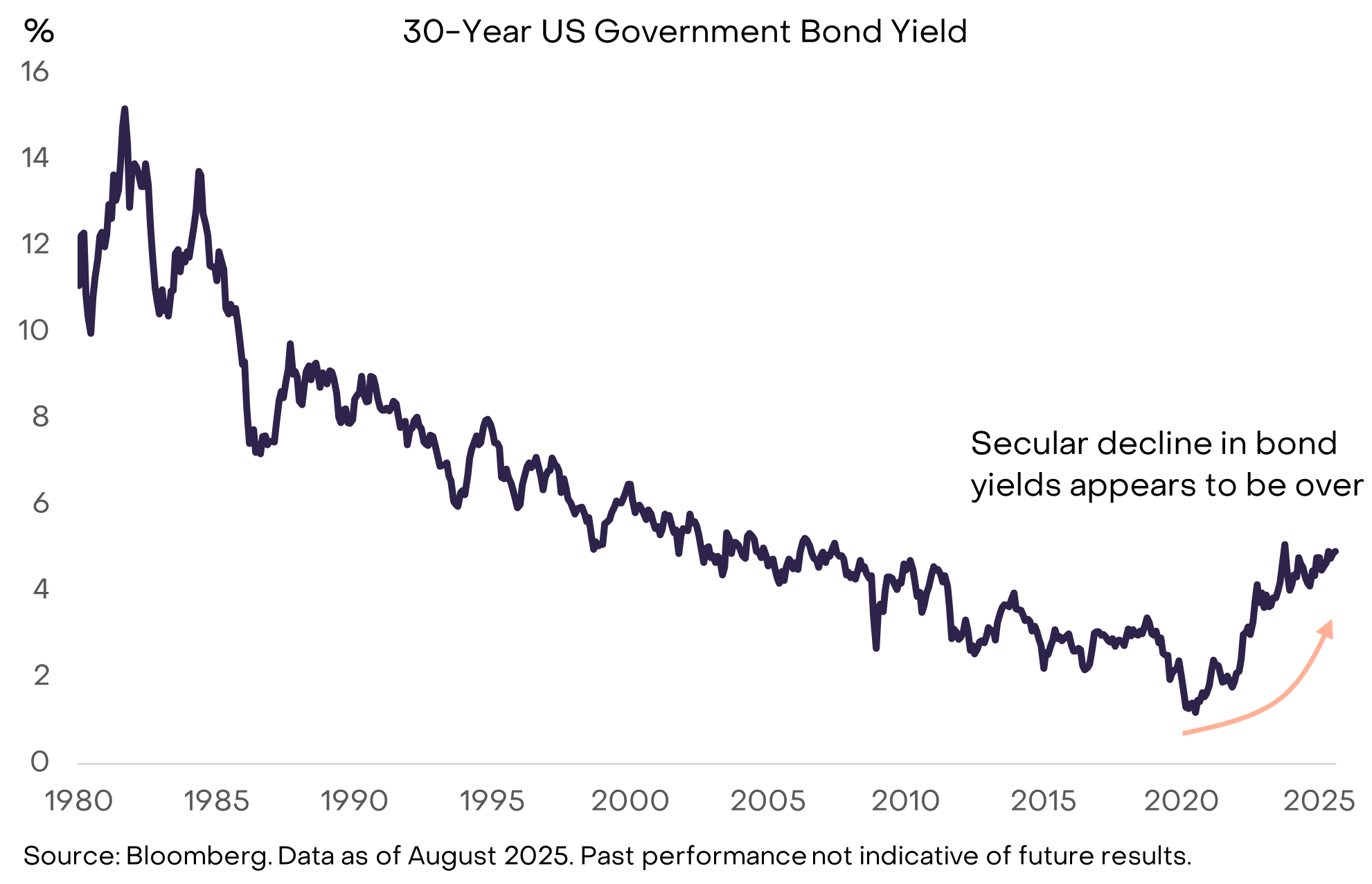

Economic theory cannot tell us how much government debt is too much. As any borrower knows, it’s not the amount of debt that matters so much as the cost of financing it. If the U.S. government could still borrow at very low interest rates, debt growth could possibly continue without material implications for institutional credibility and financial markets. In fact, some prominent economists offered a benign perspective on the rising debt stock in recent years, precisely because low interest rates made it easier to finance.[6] However, the multidecade trend of falling bond yields now seems to be over, so the limits of debt growth are starting to bind (Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6: Rising bond yields mean the constraints on debt growth are starting to bind

Like other prices, bond yields are ultimately a function of supply and demand. The U.S. government continues to supply more debt and, at some point in the last several years, it seems to have satiated demand for that debt (at low yields/high prices).

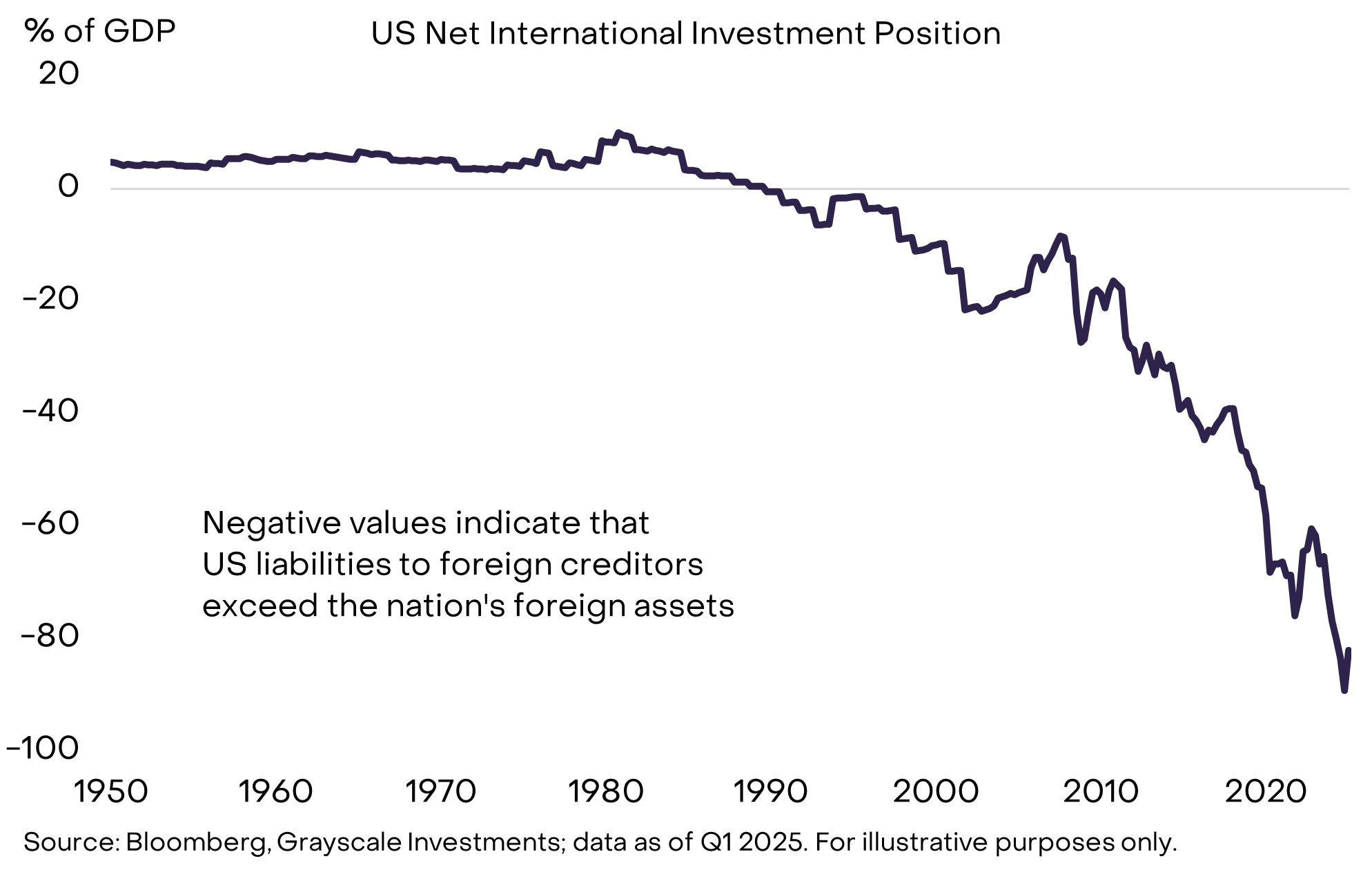

There are many reasons for this, but the critical fact is that the U.S. government borrows both from domestic savers and from abroad. There is not nearly enough domestic savings to absorb all the need for borrowing and investment in the U.S. economy. Therefore, the U.S. has both a large public debt stock and a large net debtor position in its international accounts (Exhibit 7).[7] Over the last several years, a variety of changes in foreign economies have meant that there is less international demand for U.S. government bonds at very low interest rates. These changes include the slowing of official reserve accumulation in emerging markets and the end of deflation in Japan. Geopolitical realignment may also weaken the structural demand for U.S. government bonds among foreign investors.[8]

Exhibit 7: The U.S. relies on foreign savers to finance borrowing

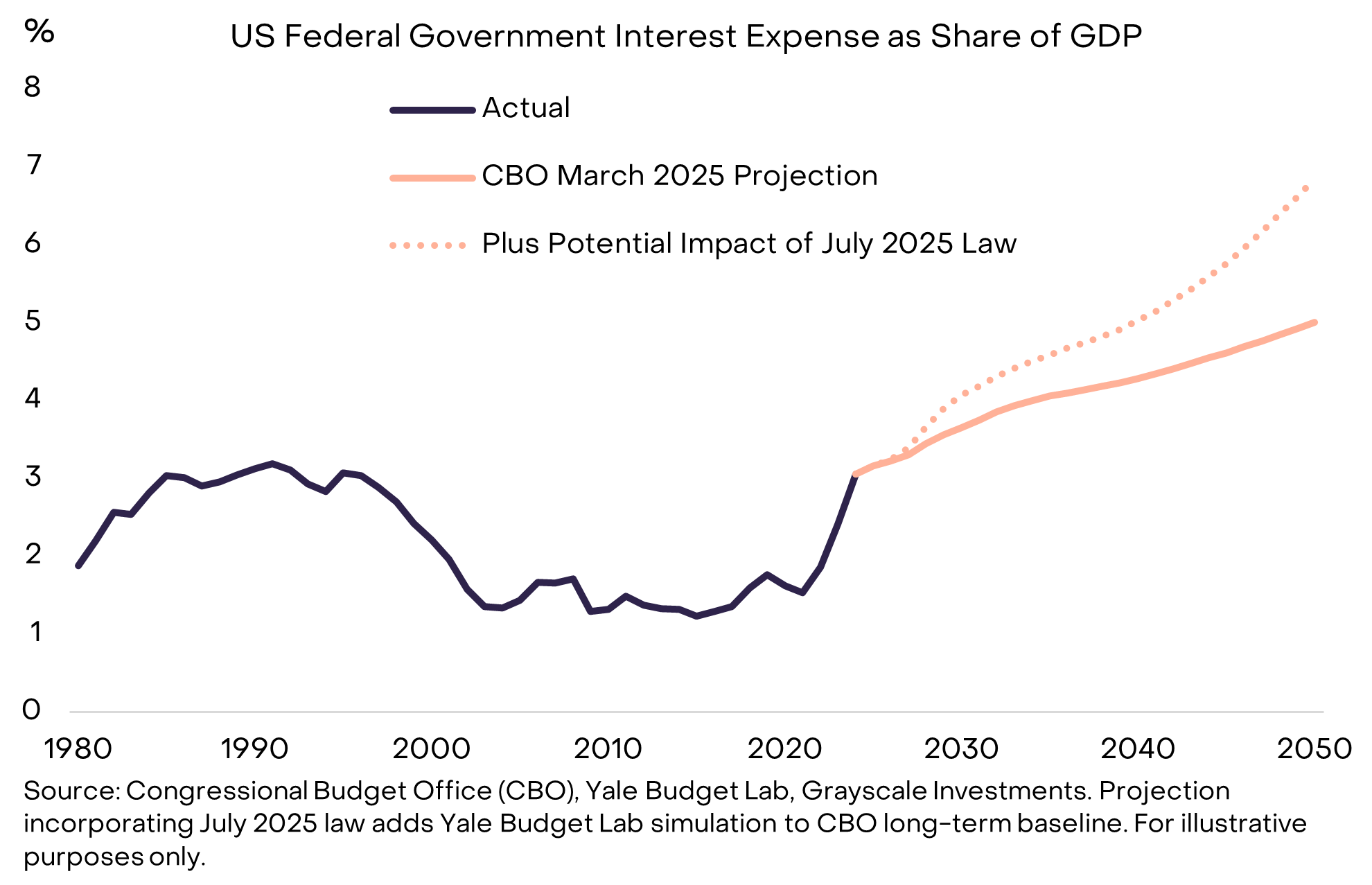

As the U.S. government refinances its debt at higher interest rates, a greater share of outlays is directed toward interest expenses (Exhibit 8). Low bond yields allowed the debt stock to increase rapidly for nearly 15 years without major consequences for the government’s interest expense. But that is now over, which is why the debt problem has become more pressing.

Exhibit 8: Higher interest expense is the binding constraint on debt growth

To get the debt burden under control, legislators need to (1) balance the primary deficit (i.e., the budget balance excluding interest payments) and (2) hope that interest costs remain low relative to growth rate of the economy. The U.S. continues to run a primary deficit (of about 3% of GDP), so the debt stock will keep rising even with manageable interest rates. Unfortunately, the latter issue — which economists sometimes refer to as the “snowball effect” — is also becoming more challenging.

Assuming the primary deficit is balanced, then the following conditions hold:

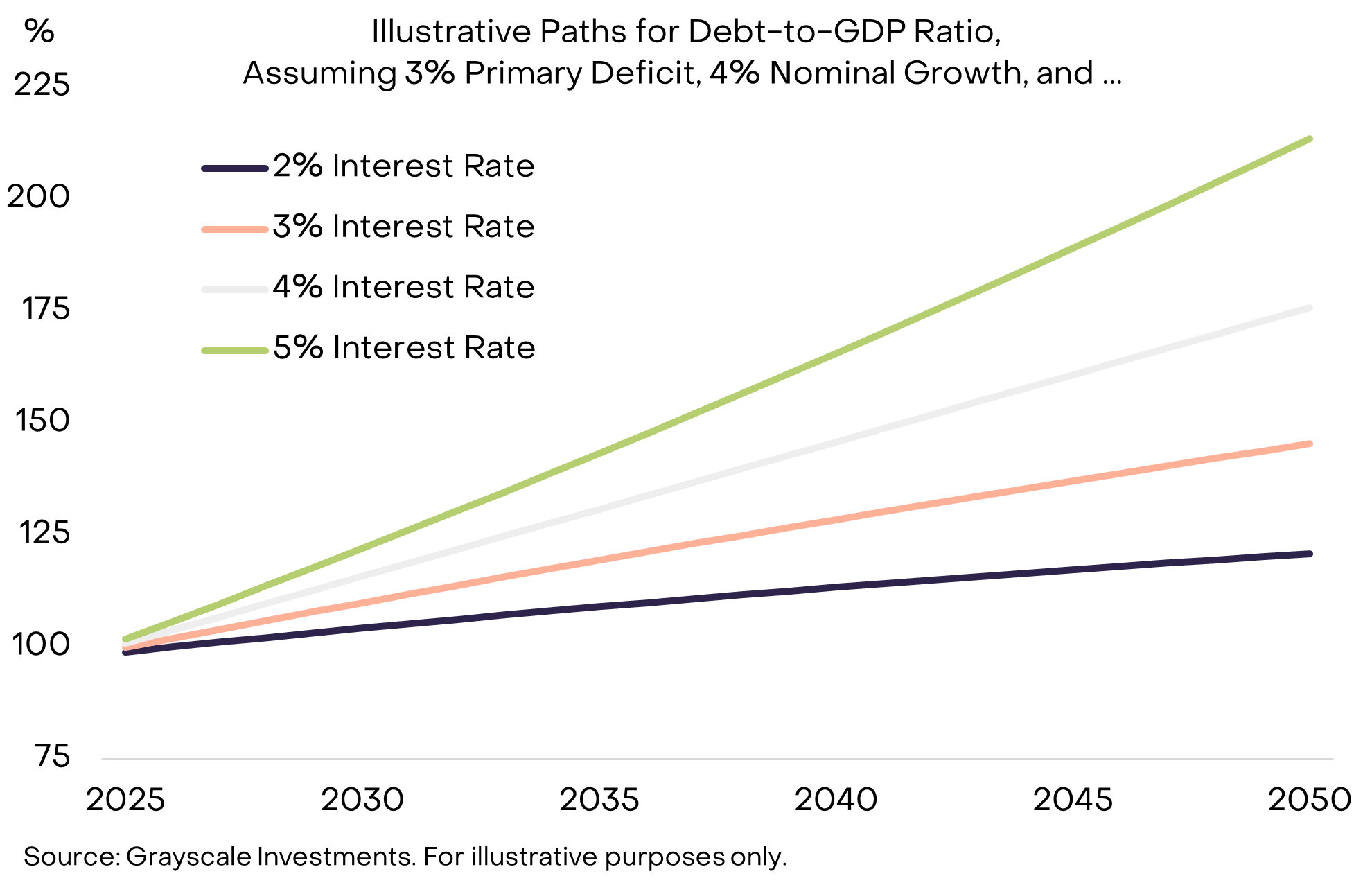

To illustrate how important this is, Exhibit 9 shows hypothetical paths for U.S. public debt as a share of GDP, assuming the primary deficit holds at 3% of GDP, and nominal GDP growth can be sustained at 4%. The bottom line: the debt burden rises much faster when interest rates are high relative to nominal growth.

Exhibit 9: Debt burden may snowball at higher interest rates

Alongside the increase in bond yields, many forecasters now expect slower structural GDP growth because of an aging workforce and reduced immigration: the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that potential labor force growth will slow from about 1% per year currently to about 0.3% by 2035.[9] Assuming the Federal Reserve can achieve its 2% inflation target — an open question — lower real growth would imply lower nominal growth and faster growth in the debt stock.[10]

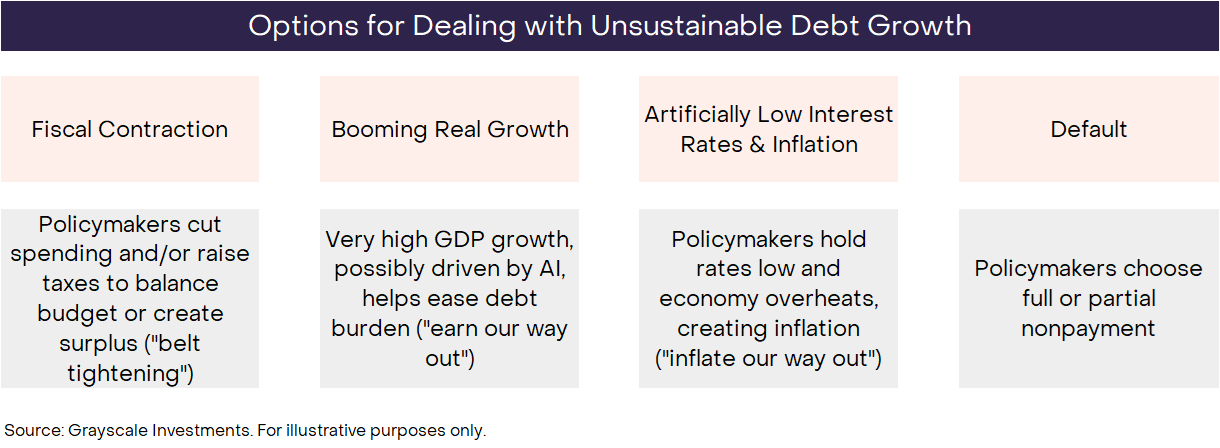

By definition, unsustainable trends cannot last forever. Unchecked growth in U.S. federal government debt will end at some point, but no one can be sure exactly how. As always, investors need to consider all the possible outcomes and weigh their probabilities, informed by the data, policymaker actions, and the lessons from history. There are essentially four possible outcomes, not necessarily mutually exclusive (Exhibit 10).

Exhibit 10: Investors need to consider the outcomes and weigh their probabilities

Default is very unlikely because U.S. debt is denominated in Dollars and inflation is typically less painful than non-payment. Fiscal contraction is possible down the road — and will probably be part of the solution eventually — but Congress just enacted the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which keeps fiscal policy on track for high deficits over the next 10 years. At least for now, reducing deficits through higher taxes and/or lower spending does not appear likely.[11] Booming economic growth would be the ideal outcome, but growth is sluggish now and potential growth is expected to slow. While not visible in the data yet, an exceptionally large surge in productivity driven by AI technology could certainly help manage the debt burden.

That leaves artificially low interest rates and inflation. For example, if the U.S. could maintain ~3% interest rates, ~2% real GDP growth, and ~4% inflation, it could theoretically stabilize the debt stock at current levels without reducing the primary deficit. The Federal Reserve is structured to operate independently to insulate monetary policy from short-term political pressures. However, recent debates and actions by policymakers have raised concerns among some observers that this independence could be at risk.[12] In any case, it may be unrealistic for the Fed to completely disregard the nation’s fiscal policy problems. History shows that, when push comes to shove, monetary policy is subordinate to fiscal policy[13], and the path of least resistance may be to inflate our way out.

Given the range of possible outcomes, the severity of the problem, and the actions of policymakers to date, it looks increasingly likely, in our view, that the strategy for managing the nation’s debt burden over time will result in average inflation above the Fed’s 2% target.

To summarize, because of the large debt stock, rising interest rates, and a lack of other viable means for dealing with it, the U.S. government’s commitment to control money supply growth and inflation may no longer be fully credible. The value of fiat currencies ultimately depends on the government’s credible commitment not to inflate the money supply. Therefore, if there is reason to doubt that commitment, investors in all U.S. Dollar-denominated assets may need to consider what it means for their portfolios. If they begin to think that the Dollar is less reliable as a store of value, they may seek out alternatives.

Cryptocurrencies are digital commodities grounded in blockchain technology. There are many different types, with use cases that often have little to do with “store of value” money. For example, public blockchains can be used for applications ranging from payments to video games to AI. Grayscale categorizes crypto assets according to their primary use case using our Crypto Sectors framework, developed in partnership with FTSE/Russell.

A small subset of these digital assets can be considered viable stores of value, in our view, because of sufficiently broad adoption, a high degree of decentralization, and limited supply growth. This includes the two largest crypto assets by market capitalization, Bitcoin and Ethereum. Like fiat currencies, they are not “backed” by some other asset that gives them value. Instead, they derive their utility/value from the fact that they allow users to make peer-to-peer digital payments without the risk of censorship and because they make credible commitments not to inflate supply.

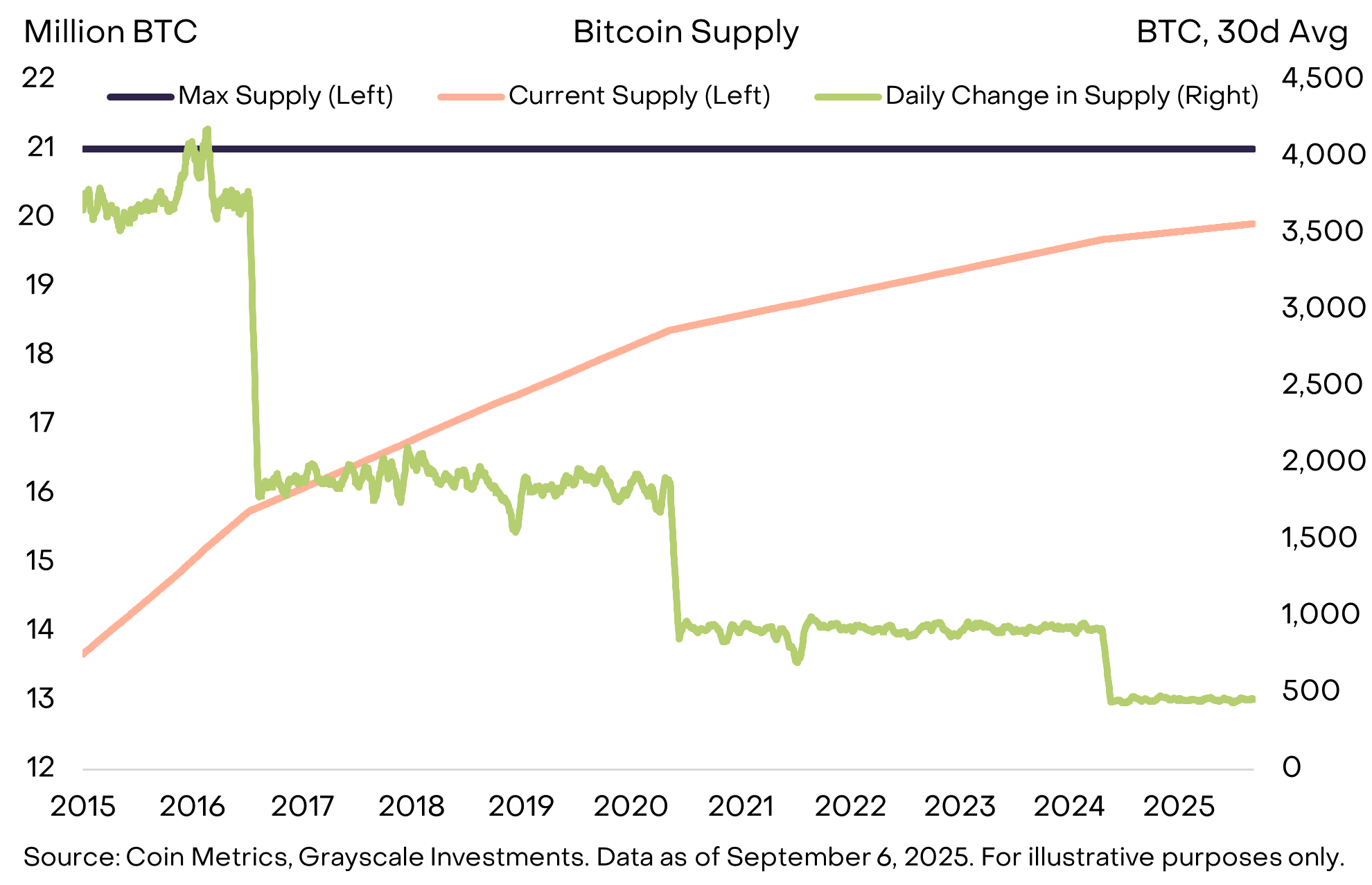

The supply of Bitcoin, for example, is capped at 21 million coins, the supply currently grows at a rate of 450 Bitcoin per day, and every four years[14] the rate of new supply falls by half (Exhibit 11). This is spelled out transparently in open-source code that is not possible to change without the consensus of the Bitcoin community. Moreover, Bitcoin is not beholden to any outside institution — like a fiscal authority needing to service its debts — that could interfere with the goals of low and predictable supply growth. Transparent, predictable, and ultimately limited supply is a simple yet powerful concept that has helped Bitcoin grow to a market cap of more than $2 trillion.[15]

Exhibit 11: Bitcoin offers predictable and transparent money supply

Like gold, Bitcoin does not pay interest[16] and is not (yet) commonly used for day-to-day payments. The utility of these assets comes from what they do not do. Most importantly, they will not increase in supply because a government needs to service its debt — there is no government, or any other institution, that controls their supply.

Investors today must navigate an environment characterized by large macroeconomic imbalances, the most important of which is unsustainable public debt growth and its implications for the credibility and stability of fiat currencies. The purpose of holding alternative monetary assets in a portfolio is to provide a ballast against the risk of fiat currency debasement. As long as those risks are getting larger, the value of assets that can provide a hedge against that outcome arguably should be going higher.

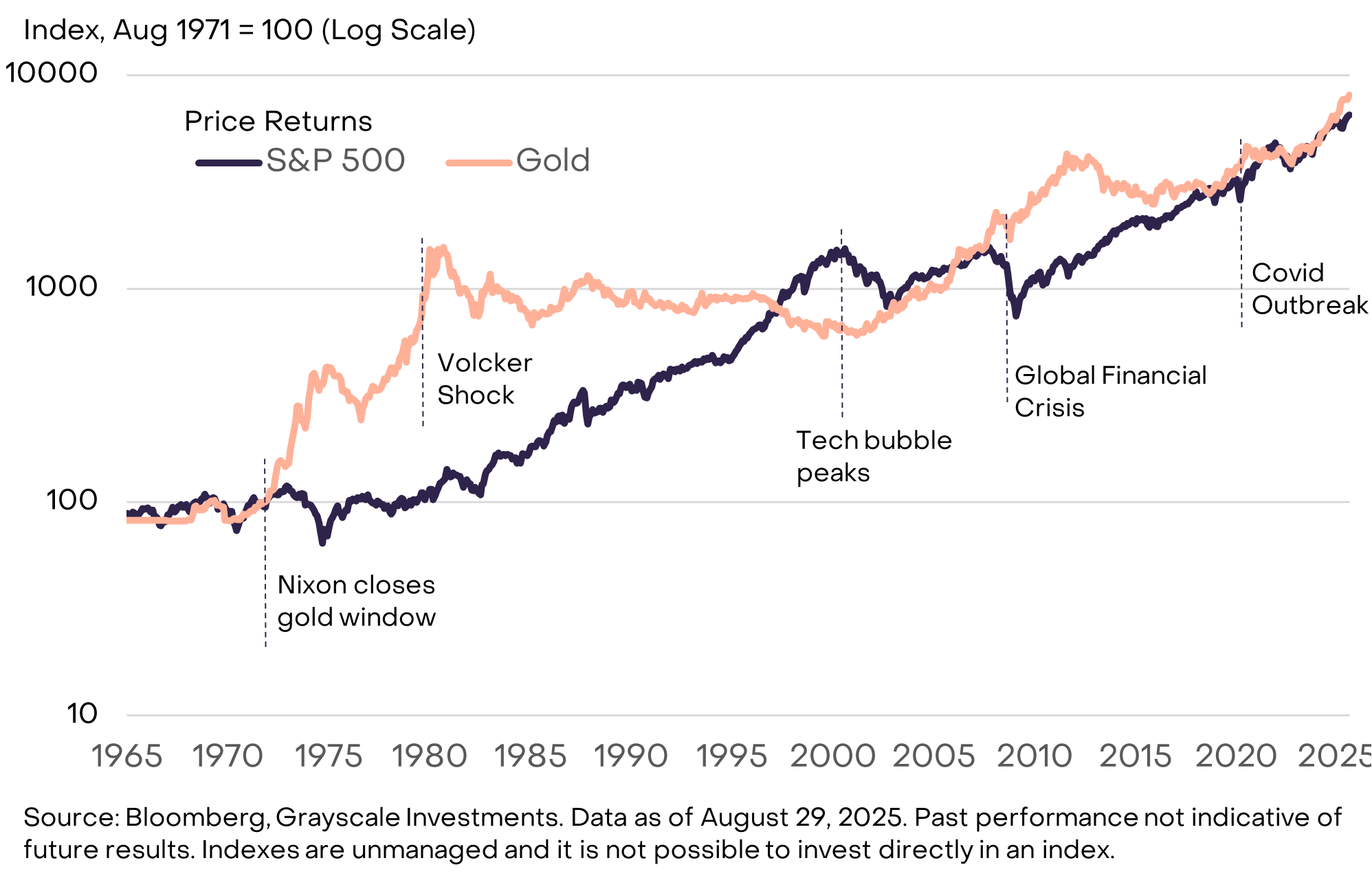

Investing in the crypto asset class involves a variety of risks beyond the scope of this report. From a macro standpoint, however, one key risk to the long-term value proposition of certain crypto assets could be that governments strengthen their commitments for managing the supply of fiat money in ways that restore public confidence. Such steps would likely entail stabilizing and then reducing government debt relative to GDP, reiterating support for the central bank’s inflation target, and taking steps to buttress central bank independence. Government-issued fiat currency is already a convenient medium of exchange. If governments can ensure that it will also be an effective store of value, demand cryptocurrencies and other alternative stores of value may decline. For example, gold performed well during the 1970s when U.S. institutional credibility was in question but performed poorly in the 1980s and 1990s as the Fed got inflation under control (Exhibit 12).

Exhibit 12: Gold performed poorly in the 1980s and 1990s alongside falling inflation

Public blockchains provide innovations in digital money and digital finance. The blockchain applications with the highest market value today are digital money systems that offer features distinct from fiat currencies — and demand has been associated with factors including modern macroeconomic imbalances like high public sector debt. Over time, we believe that growth in the crypto asset class will be driven by both these macro factors and the adoption of other innovative public-blockchain-based technologies.

[1] The asset of the Ethereum network is called Ether.

[2] Former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan famously said: “Price stability is that state in which expected changes in the general price level do not effectively alter business or household decisions.” Source: Federal Reserve.

[3] Source: Federal Reserve.

[4] Source: Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Data for fiscal year 2025. For illustrative purposes only.

[5] Source: Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Data for fiscal year 2025. For illustrative purposes only.

[6] See for example Furman and Summers (2020).

[7] The international investment position includes both public and private sector assets and liabilities.

[8] The amount of Dollars held by nation states is partly a function of their international relations and military alliances. See for example Eichengreen (2017).

[9] Source: Congressional Budget Office. Data as of 2025. For illustrative purposes only.

[10] Source: Federal Reserve.

[11] The Trump Administration has increased US tariffs. This raises revenue and therefore, all else equal, helps balance the primary deficit. However, the extent to which tariffs can be used for long-term fiscal sustainability remains an open question, because they have been challenged in court, may keep interest rates elevated (because of the impact on inflation), and could contribute to geopolitical realignment that reduces foreign demand for US Treasuries.

[13] See for example Sargent and Wallace (1981).

[14] Technically every 210,000 blocks, which corresponds to roughly every four years.

[15] Source: Coin Metris. Data as of September 10, 2025.

[16] Ether, the asset of the Ethereum network, can be staked, which can generate additional earnings for holders from the validation services they provide.