Last Updated: 7/21/2025 | 38 min. read

Everyone benefits from greater efficiency in the economy’s payments system, but fundamental changes are hard to come by. By its nature the payments system is a network with many participants, so reform efforts can face significant coordination challenges. Even seemingly obvious improvements — like common messaging standards and overlapping operating hours between global banks — are difficult to implement. For the last five years, the G20 group of nations has had an explicit goal of improving cross-border payments — which can be especially frustrating for users — but progress has been slow.[1]

Stablecoins are an emerging innovation in digital payments based on blockchain technology. Like most crypto applications, stablecoin adoption has been a bottom-up phenomenon: a diverse range of users around the world are finding benefits from transacting with and/or storing value in stablecoins. The GENIUS Act, which was signed into law by President Trump on Friday July 18, provides a comprehensive regulatory framework for payment stablecoins in the U.S. This legislation and similar efforts in other countries will allow stablecoins to integrate more deeply into the traditional financial system, while putting in place the appropriate safeguards for financial stability, consumer protection, and the prevention of illicit activity.

Grayscale Research believes stablecoins can disrupt aspects of the global payment industry by offering lower costs, faster settlement times, and greater transparency. We expect stablecoins to make the biggest inroads in (1) cross-border payments; (2) domestic payments in markets dominated by credit cards, like the United States; and (3) the transfer of value between artificial intelligence (AI) agents. Stablecoins are also a way to hold digital value and may partly disintermediate commercial bank deposits. Within the crypto ecosystem, the biggest beneficiaries are likely to be stablecoin issuers and their distribution partners, who earn net interest margin (NIM), as well as blockchains in the Ethereum ecosystem, certain other high-performance Layer 1s, and related decentralized finance (DeFi) applications like oracles and decentralized exchanges (DEXs).

Stablecoins are digital tokens tied to the Dollar and issued on a blockchain. There are many types of stablecoins (discussed below), but mainstream users are likely to interact with one specific type: fully collateralized fiat-backed stablecoins. These instruments closely resemble government-only money market mutual funds: they are stable-dollar-value tokens fully backed by Treasury bills or comparable collateral (Exhibit 1). Stablecoins maintain their peg to the Dollar because the stablecoin issuer always stands ready to redeem stablecoins at par or issue more stablecoins in exchange for cash. This is a very simple structure, and not a particularly interesting innovation in itself. However, when tokenized digital dollars are deployed on a public blockchain, they gain the blockchain’s functionality, which includes borderless payments, near-instant settlement, potentially low cost, and a high degree of transparency.

Exhibit 1: Regulated U.S. payment stablecoins will have simple structure

Today stablecoins are ubiquitous in the context of crypto trading. For example, for crypto tokens traded on centralized exchanges (CEXs), a stablecoin is one side of the pair for 70%-80% of volume.[2] Therefore, growth in crypto trading volume will very likely result in growth in stablecoin balances and transaction volumes. Stablecoins are also a primary tool for users to access DeFi applications like decentralized lending protocols. However, stablecoins are now also being used for conventional digital payments, especially in emerging market economies.[3] This use case is independent of speculative crypto trading and may therefore support sustainable growth in blockchain adoption.

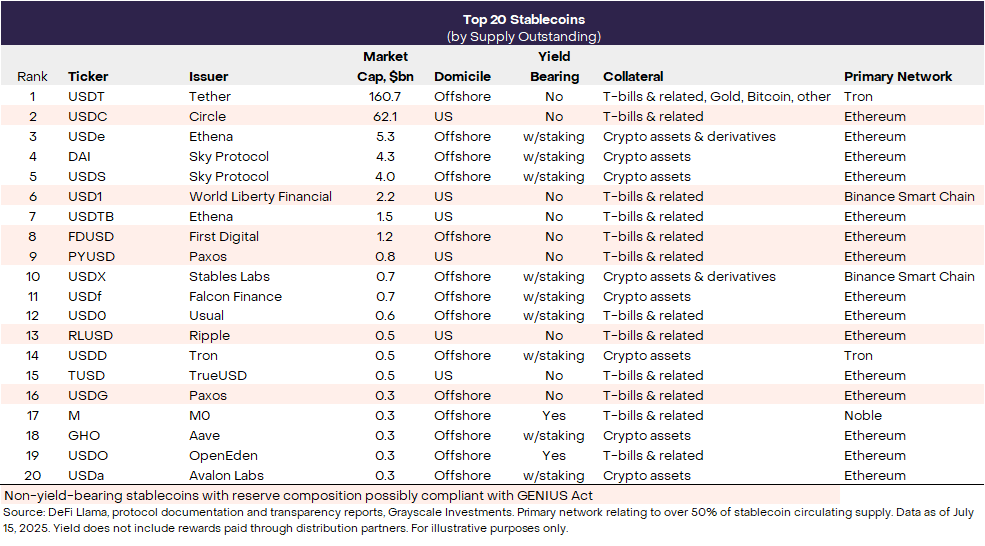

Although issuers have created stablecoins for many currencies, virtually all the $250 billion in stablecoins outstanding are U.S. Dollar instruments.[4] Two issuers dominate the market for Dollar stablecoins: Tether, issuer of the USDT stablecoin, and Circle, issuer of the USDC stablecoin (Exhibit 2). Tether is domiciled offshore and its USDT stablecoin accounts for about 60% of total stablecoin “market cap” (supply outstanding). Circle is domiciled in the U.S. and its USDC stablecoin accounts for about 25% of total market cap.[5] Tether is now a major holder of U.S. Treasury securities in its reserves: if it were a nation, it would be the 18th largest foreign holder of Treasuries, just after Saudi Arabia and ahead of South Korea.[6]

Exhibit 2: The largest stablecoins are USDT and USDC

There is no perfect measure of stablecoin transaction volumes,[7] but a consortium of crypto data specialists, in partnership with Visa, have created a widely used benchmark that seeks to remove certain types of bias (e.g., high-frequency traders and bots). According to these estimates, users made more than 120 million stablecoin transactions in June 2025 (Exhibit 3).[8] The total value transferred amounted to about $800 billion, or nearly $10 trillion on an annualized basis. For comparison, the Visa network processed about $13 trillion in payments volume in 2024.[9] To be clear, these transactions relate to both crypto trading and payments use cases, and it is not possible to distinguish between them with on-chain data alone. At present, the large majority of stablecoin transactions are likely still related to crypto trading (possibly as much as 90%),[10] rather than payment for goods and services.

Exhibit 3: More than 100 million stablecoin transactions per month

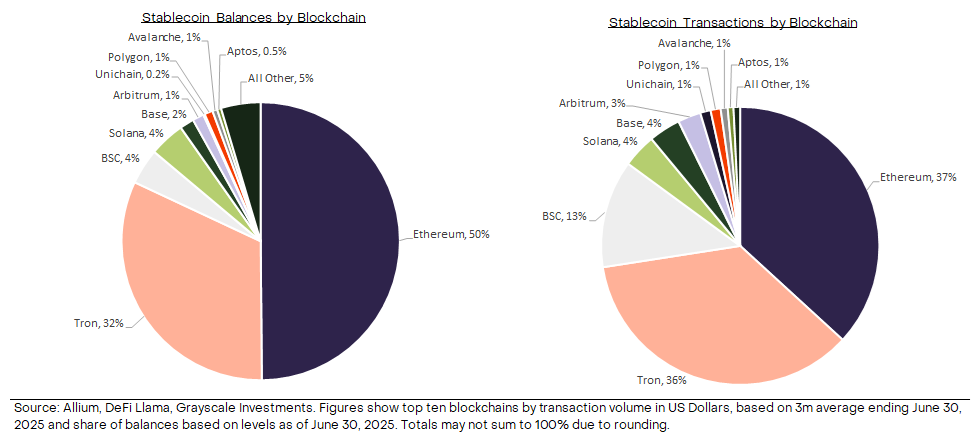

Stablecoins are used on most smart contract platform blockchains, but the current category leaders are Ethereum and Tron (Exhibit 4). About half of all stablecoin balances are held on Ethereum, consisting of both USDT and USDC; virtually all the stablecoin balances on Tron consist of USDT. Year to date Ethereum and Tron have both processed about $1.7 trillion in stablecoin transactions; most Tron transactions are in Tether’s USDT stablecoin (>99%), and most Ethereum transactions are in Circle’s USDC stablecoin (~65%).[11]

Exhibit 4: Ethereum and Tron are the leading blockchains for stablecoins today

The modern global economy couldn’t function without an effective payments system, and the existing infrastructure works well enough to keep it running smoothly. At the same time, there’s room for improvement in specific areas. The most glaring example is cross-border payments — which is why the G20 makes this issue an explicit focus — but there are inefficiencies in certain domestic payment networks too. Moreover, growth in transactions by AI agents will create new demands on the economy’s payments infrastructure. Stablecoins could help drive efficiencies in segments of global payments, possibly reducing costs for consumers and businesses.

Cross-border payments involve financial institutions (and their regulations) in multiple countries, so they are typically more complex than domestic payments. Because of this complexity, cross-border payments tend to be more expensive, slower to settle, and often opaque for users. The most common type of cross-border payment involves a correspondent bank, which maintains accounts for partner banks in each domestic market and settles transactions between them (Exhibit 5). In some cases, multiple correspondent banks will link financial institutions in distant markets.[12]

Exhibit 5: Cross-border payments involve multiple intermediaries

Source: Grayscale Investments. For illustrative purposes only.

Every additional intermediary in the process adds potential costs and delays. The Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international body, reports aggregate data on the cost of cross-border payments in its annual reports.[13] Excluding remittances, the average cost of a person-to-business cross-border payment in 2024 was 2% and the average cost of a person-to-person cross-border payment was about 2.5%. For remittances, the average cost was around 5%.[14] For many cross-border payments, speed is not a problem: around 70% of retail payments are available within one business day of payment initiation, according to the annual FSB report. However, there’s a tail of payment corridors with median processing times of more than two days[15] and potentially lasting as many as 10 days.[16] Stablecoins could potentially offer lower costs and faster settlement times in these cases.

In our view, there’s also scope for improvement in domestic payment systems, like in the United States, that are dominated by credit card networks. Credit card networks are highly concentrated, which may allow providers to maintain margins, and regulators and elected officials frequently explore ways to reduce costs.[17] Stablecoins could add competition to these markets and help drive down costs for users.

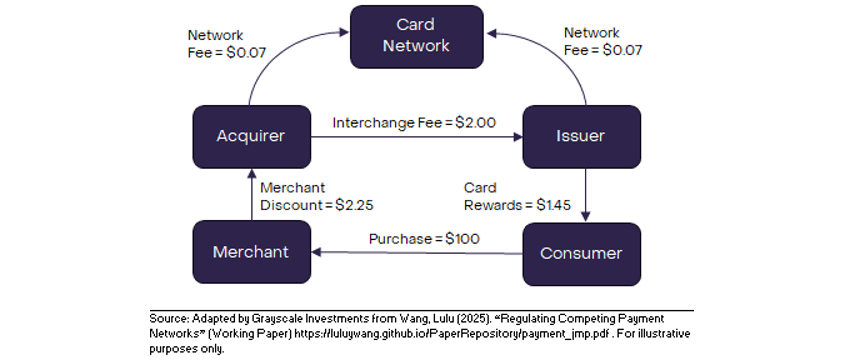

The diagram below shows the structure of a typical U.S. credit card payment and the flow of associated fees. When a consumer spends $100, the merchant typically receives $97.75 and pays the remaining $2.25 (the so-called merchant discount) to the card acquirer (the financial institution that processes transactions on behalf of the merchant). A portion of this total ($1.45) is returned to consumers in the form of card rewards. The remainder ($0.80) is earned as revenue by the banks and credit card companies that make up the network. Although many consumers enjoy the card rewards from this system, merchants may have an incentive to seek out alternative forms of digital payment. In addition, policymakers may be concerned that this system benefits card users (who earn the rewards) at the expense of cash users (who in most cases still pay the same final retail price).

Exhibit 6: Credit card payments involve several different fees

Finally, the traditional payments system is not well suited for AI agents—autonomous software that can act independently and carry out complex instructions. As non-human actors, AI agents cannot legally own or operate bank accounts. In contrast, blockchains allow for AI agents to autonomously control wallets and allocate financial resources. Blockchains also support microtransactions with near-instant finality, unlike traditional systems, which involve multi-day settlement times and high fees. As a result, stablecoin payments on blockchains can both improve upon and significantly expand the scope of what AI agents can do. While this is a new use case for the global payments system, some analysts expect rapid growth over the coming years,[18] which could make AI agent payments a major use case for stablecoins (for more background, see When You Give an AI a Wallet).

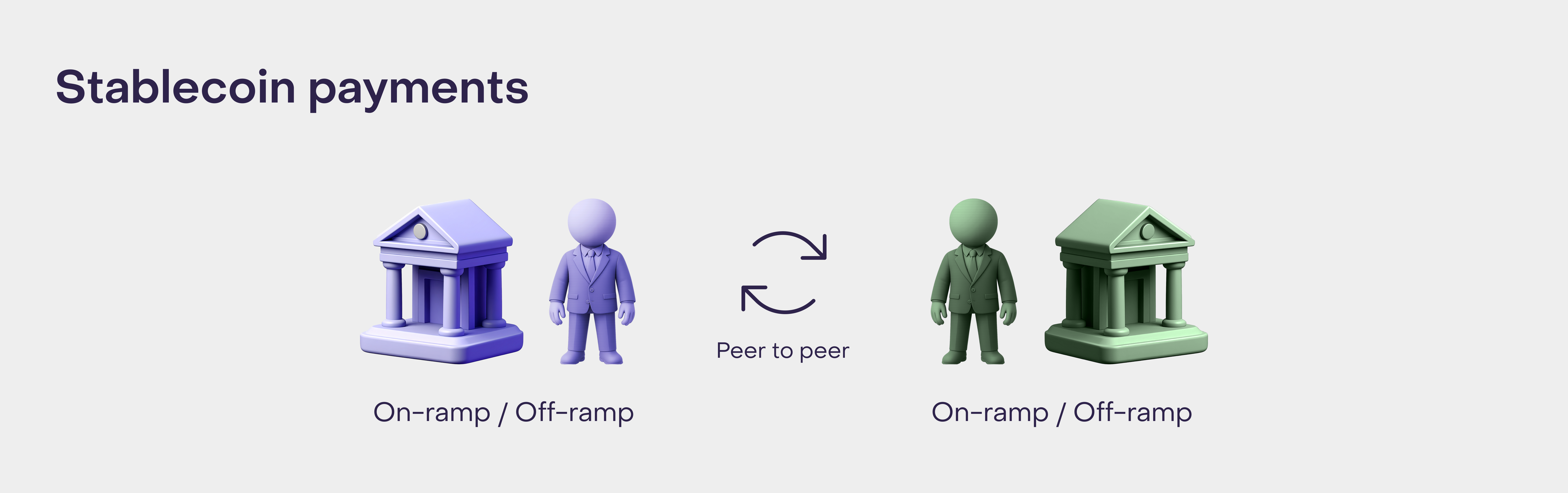

Stablecoins on public blockchains offer an entirely different structure for digital payments. In payments industry jargon, stablecoins are an innovation at the “back end” (the underlying infrastructure layer), whereas many other recent innovations have focused on the “front end” (the consumer interface layer). Stablecoin transfers on a blockchain are fully peer-to-peer with no intermediary processing the transaction (Exhibit 7). However, users may need to first “on-ramp” funds to the blockchain through a financial institution and later “off-ramp” funds to spend them. Users will opt for stablecoin-based payments if they offer (1) lower end-to-end total costs, (2) faster speeds, and/or (3) lower risk of payment failure.

Exhibit 7: Stablecoin payments are peer-to-peer

Source: Grayscale Investments. For illustrative purposes only.

Smart contract platform blockchains process transactions relatively quickly and at a relatively low cost (Exhibit 8). Blockchain transaction costs do not scale 1:1 with the value of transactions, so high-value transactions will tend to have lower fees in percentage terms. For users that do not need to on/off-ramp, stablecoins on public blockchains are already a highly efficient means for transferring digital value around the world. If stablecoin adoption grows, and more merchants accept stablecoins for goods and services, the need to off-ramp to bank-based payment rails may decline, allowing more users to get the benefits of stablecoin transactions on a blockchain.

Exhibit 8: Smart contract blockchains offer fast and cheap transactions

In practice, however, most merchants don’t yet accept stablecoins for payment, and users need to off-ramp funds to make them spendable. When transacting with stablecoins, users therefore need to consider the full end-to-end cost, inclusive of on-ramping and/or off-ramping. While technically a simple process, financial institutions often charge fees for on/off-ramping to cover the cost of compliance: intermediaries are responsible for implementing policies and procedures for anti-money laundering (AML) and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT), as well as any applicable sanctions-related restrictions and other capital controls. Intermediaries may also need to cover costs related to payments fraud and other overhead. For all these reasons, the end-to-end cost of a stablecoin transaction will not be cost competitive with traditional payment rails in all circumstances.

Many large crypto-financial institutions, like Coinbase (the largest exchange in the U.S.) and Mercado Bitcoin (the largest exchange in Latin America) offer zero-fee on-ramping and off-ramping services in stablecoins and potentially other assets.[19] For transactions with zero-fee on-ramping and off-ramping, stablecoin transactions may be significantly cheaper than traditional payment rails. In other circumstances, on/off-ramp fees can be around 1% for each leg, in which case the cost/benefit would depend on the specific circumstances.[20] In certain other cases, these fees can exceed 5%, in which case stablecoins may not be cost effective compared to traditional alternatives. Lower average on/off-ramping costs over time could be a factor supporting continued stablecoin adoption.[21]

Grayscale Research expects stablecoins to make deep inroads into traditional payments, but they are unlikely to be competitive in all market segments (especially in the near term, while some related blockchain infrastructure is in development). Stablecoin dominance in the context of crypto trading is already high and may increase further. For payments use cases, we expect stablecoins to be most competitive in three areas:

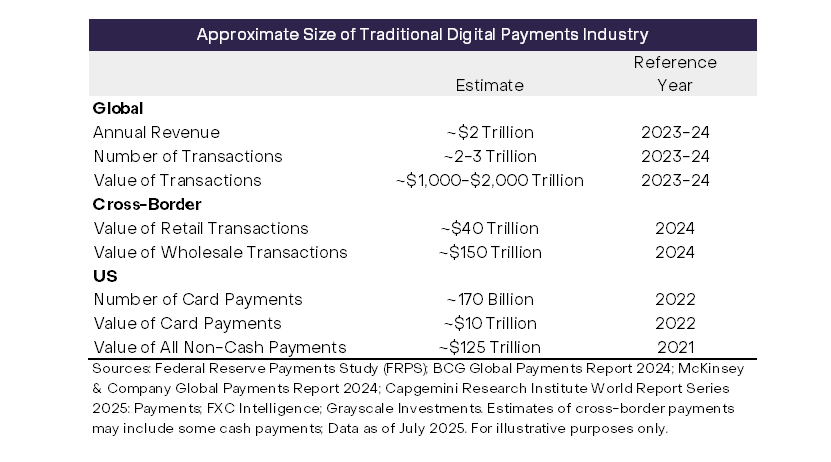

It’s challenging to be precise about stablecoins’ total addressable market (TAM), but data from the existing payments systems can give us a sense of the possible scale. Exhibit 9 shows our rough estimates based on a variety of sources.[22] The global payments industry processes 2-3 trillion transactions per year for a total value of $1,000-$2,000 trillion (i.e., $1-$2 quadrillion). The industry earns about $2 trillion in revenue, which is split roughly between net interest margin (NIM) and transaction fees.[23]

Exhibit 9: Global payments industry processes 2-3 trillion transactions per year

The stablecoin industry is still very small by comparison. Stablecoin transactions currently total about 100 million per month (~0.05% of traditional payments) for a total Dollar value of about $800 billion per month (~0.5%-1.0% of traditional payments).[24]

Stablecoin issuers likely earn about $10 billion to $12 billion annually in gross interest revenue, based on a 4%-5% U.S. cash interest rate and $250 billion in stablecoin outstanding. Most stablecoins do not pay interest, so gross interest and NIM are likely comparable (although stablecoin issuers have other operating expenses). We separately estimate that blockchains processing stablecoin transactions will likely earn only about $0.5 billion at an annual rate from this activity (i.e., not including fees from other transactions).[25]Therefore, total stablecoin industry revenue equates to only about 0.5% of the revenue of the traditional payments industry.

Rising stablecoin adoption should support both NIM and transaction revenue. Under the GENIUS Act, regulated payment stablecoins in the U.S. cannot pay interest directly. Therefore, stablecoin issuers may be able to maintain healthy NIMs for the time being. However, competitive pressures may ultimately result in some sharing of interest revenue with distribution partners (as Circle does with Coinbase) and eventually with users. Net interest income may therefore grow more slowly than the supply of stablecoins outstanding. The NIM earned by stablecoin issues comes mostly at the expense of commercial banks, which currently issue the digital Dollars held for transaction use by the public.

In contrast, transaction revenue should grow roughly in-line with rising transaction volumes, in our view.[26] If stablecoins were to capture 20% of the transaction volume processed over traditional payment rails, for example, that would amount to about 500 billion transactions annually. At a weighted-average fee of $0.10 (see again Exhibit 8), 500 billion transactions amount to $50 billion in annual transaction fees — or about a 100x increase in the revenue smart contract platform blockchains earn from stablecoin activity today.[27]

Ethereum hosts the largest number of stablecoins and processes the most stablecoin transactions. It is also diversified across USDC, USDT, and a number of smaller stablecoins. Therefore, the Ethereum Ecosystem seems very likely to benefit from rising stablecoin adoption. This includes the Ethereum Layer 1, which is likely to be favored for high-dollar-value transactions and those with the highest security requirements, and Ethereum Layer 2s, which offer lower-cost and high-speed transactions. Today the largest Ethereum Layer 2 networks for stablecoins are Base, Arbitrum, and the OP Mainnet.

Stablecoin activity is unlikely to remain confined to the Ethereum ecosystem, however. Other high-performance blockchains will likely also see rising stablecoin activity, in our view, including Solana, Avalanche, Sui, and many others. These chains are popular with many users because of their low costs, high transaction throughput, and/or because of a compelling end-user experience. Particularly in consumer-oriented applications these alterative Layer 1 blockchains may have advantages over the Ethereum Layer 1 or Ethereum rollups. Tron is closely associated with Tether’s USDT stablecoin, so its competitive position may depend on whether Tether takes steps to qualify USDT as a regulated payment stablecoin under the new GENIUS Act framework, or whether Tron can effectively diversify into other stablecoins.

The applications that make up the core infrastructure of DeFi should also benefit from stablecoin adoption. There is potentially a long list, but we would highlight leading oracle and messaging service Chainlink and leading Ethereum DEX Uniswap. Specialized service providers focused on stablecoins, like Paxos, Ethena, and M0, are also well positioned for further adoption.

The stablecoin opportunity is not lost on traditional fintechs—and increasingly traditional financial services firms. Earlier this year, leading payments company Stripe finalized a $1.1 billion deal to acquire stablecoin infrastructure provider Bridge, its largest acquisition ever.[28] Bridge enables companies to issue, use, and transfer stablecoins globally via their APIs. Today, Bridge customers range from startups to multinational corporations such as SpaceX, which uses stablecoins for treasury management, and ScaleAI, which uses stablecoins to pay its contractors around the world.[29]

Stripe also recently acquired Privy, a crypto wallet and on/off-ramp service provider. Stripe's vision is to make stablecoins a “scaling layer” on top of the fiat system, reducing legacy financial friction for businesses and AI applications.

In addition to Stripe, other leading fintechs involved with stablecoins include PayPal (launched its own stablecoin PYUSD in 2023 and is now the 10th largest stablecoin by market cap),[30] Fiserv (recently launched the FIUSD stablecoin),[31] Robinhood,[32] and Revolut (actively exploring launching a stablecoin)[33]. Stablecoins have also been integrated directly into the platforms of several fintechs including Robinhood (to power weekend settlements), MoneyGram, Visa, and Mastercard.[34]

Beneficiaries of stablecoin adoption could include some incumbent firms that issue their own stablecoins and are able to leverage distribution advantages or firms that integrate third-party to improve their product offerings. We believe key winners could include infrastructure players like Stripe and Paxos as well as low-cost on and off-ramping service providers such as Coinbase and Mercado Bitcoin.

The GENIUS Act provides a comprehensive regulatory framework for stablecoins in the U.S. and will likely support stablecoin adoption while preserving financial stability, protecting consumers, and preventing the use of the financial system for illicit activity. However, it is important to stress that most stablecoins have proven effective at maintaining their Dollar pegs before a complete regulatory framework was in place. Moreover, global regulatory bodies already offer detailed compliance guidelines for stablecoin issuers and related service providers, and these institutions regularly cooperate with law enforcement.

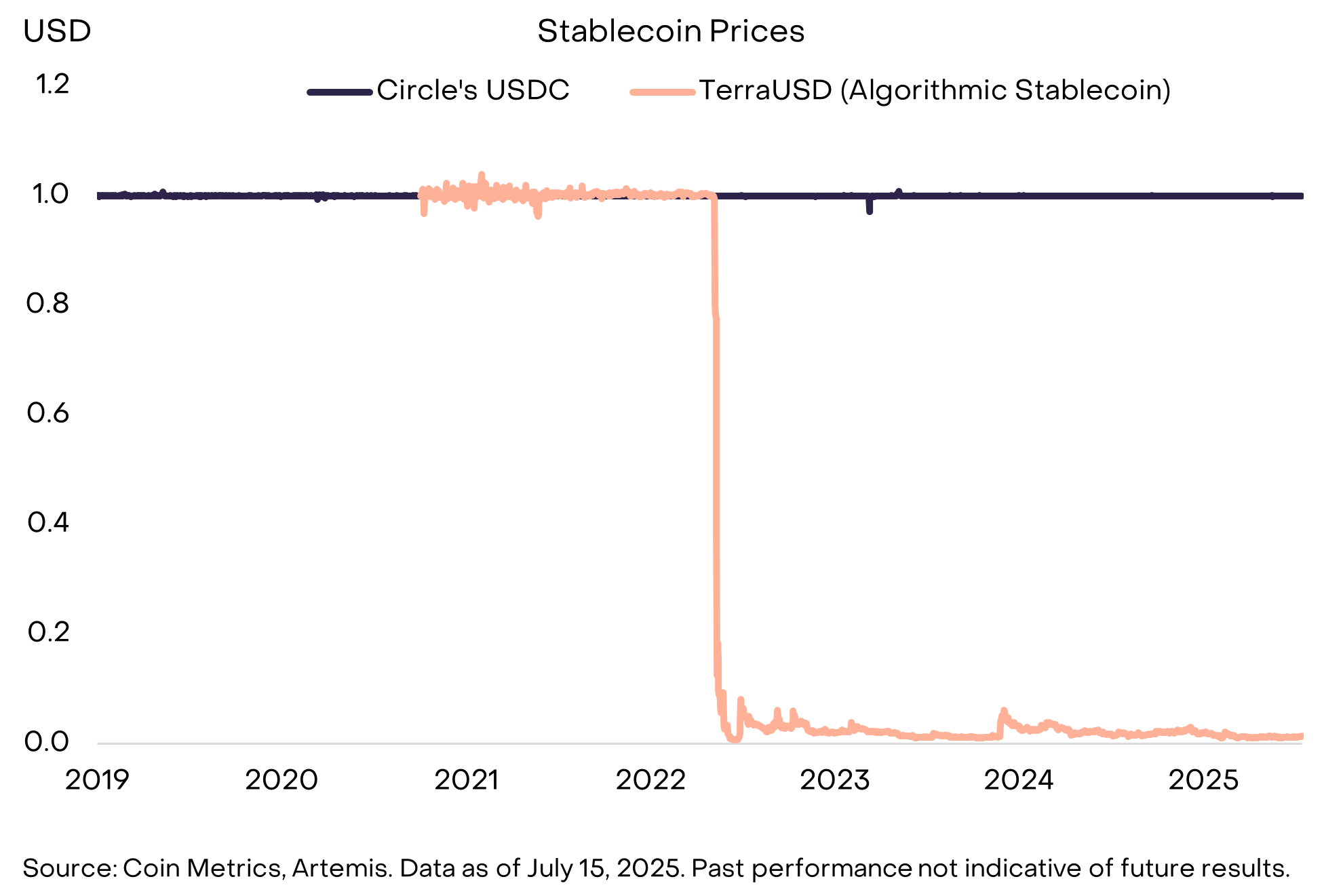

In 2022, the Terra USD stablecoin collapsed after growing its circulating supply to more than $18 billion[35] — a major black eye for the stablecoin industry. Under the GENIUS Act, this type of “algorithmic” stablecoin cannot be used as a regulated payment stablecoin and will not be integrated into mainstream consumer finance applications. Stablecoins fully collateralized with fiat currency assets (e.g., Treasury bills and cash), like Circle’s USDC, have been effective at maintaining their pegs (Exhibit 10).[36] For example, since September 2018, the price of USDC has been more than 0.25% from $1.00 less than 1% of the time, and more than 1% from $1.00 on only a single day.[37] Like government-only money market mutual funds and “currency boards” in foreign exchange,[38] stable-value instruments backed by safe and liquid collateral are typically effective at maintaining their pegs. Moreover, these narrow structures do not require the systems of deposit insurance and central bank discount window lending that support risk-taking commercial banks.

Exhibit 10: Failed stablecoins are the exception not the rule

Under the GENIUS Act, permitted stablecoin issuers must maintain reserves equal to at least 100% of outstanding stablecoins, held in clearly identifiable assets. Acceptable reserve assets include USD currency, demand deposits, short-term Treasury securities (≤93-day maturity), repurchase and reverse repurchase agreements collateralized by Treasuries, government money-market fund shares, and central bank reserve deposits.

According to the GENIUS Act, stablecoins collateralized by other stablecoins (e.g. a stablecoin with Circle USDC in its reserves) will not qualify as a regulated payment stablecoin.[39] Stablecoins that are backed by crypto assets (e.g. DAI) and/or those that incorporate derivatives (e.g. USDe) will not qualify as US payment stablecoins under the new rules, based on the current composition of their reserves (although they could potentially take steps to qualify). This leaves a relatively small number of stablecoins that would seem to qualify as a regulated US payment stablecoin based on the composition of their reserves (although issuers are also required to register with regulators, maintain various compliance policies, and otherwise meet the requirements of new law). The non-yield-bearing stablecoins with a potentially compliant reserve structure include Circle’s USDC, World Liberty’s USD1, First Digital’s FDUSD,[40] PayPal’s PYUSD, Ripple’s RLUSD, and Paxos’ USDG (Exhibit 11).

Exhibit 11: GENIUS Act requires that stablecoins have specific structure

Separately, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a global regulatory body that develops rules for AML and CFT policies, has published guidance on digital assets for approximately 10 years.[41] In effect, almost all of the standard FATF policies must be applied by financial institutions operating in digital assets, including know your customer (KYC) policies and ongoing customer due diligence. This includes the Travel Rule, which requires service providers to document and transmit specific identity information about the participants in crypto transactions. Stablecoin issuers are required to cooperate with law enforcement and freeze funds when requested. For example, in 2023 Tether froze $225 million USDT at the request of law enforcement; more recently Circle froze $58 million related to a memecoin.[42]

The GENIUS Act likewise treats each permitted stablecoin issuer as a “financial institution” under the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), making it subject to full anti-money-laundering and sanctions rules. Issuers must maintain a risk-based AML/CFT program, designate a compliance officer, monitor transactions and file Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs), retain records, verify customers under a KYC regime, and build technical controls to block, freeze, or reject illicit transfers. Treasury is directed to adopt tailored regulations, but the statutory duties — customer due diligence, SAR filing, and sanctions screening — mirror those imposed on banks.

Stablecoins are a welcome innovation in global payments infrastructure, and we expect that they will help drive down some costs and bring new consumer benefits. But there are limits to stablecoin adoption, partly because certain competing payments innovations have proven effective. Moreover, the underlying blockchain infrastructure lacks some of the features that may be needed for stablecoins to reach their full potential.

In many large countries, there are already fintech platforms offering low cost and nearly instantaneous retail payments. These include Alipay and WeChat Pay in China, the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in India, and Pix in Brazil. There are also efforts to link these systems together for more effective cross-border payments. Other fintechs specialize in cross-border payments, including Revolut, Remitly, and Wise. These services can offer cheap and fast cross-border payments when both participants maintain accounts on the platform. Lastly, stablecoins may eventually have to compete with tokenized deposits, which are another structure for digital dollars on a blockchain. Tokenized deposits are a bank-centric framework that would lack some of the benefits of stablecoins (which circulate as digital bearer assets), but they are favored by some regulators (and, naturally, by some banks).[43]

Eventually, consumers may also have a choice between stablecoins and a central bank digital currency (CBDC). The many possible types of CBDCs are beyond the scope of this report. However, in simple terms, a CBDC is another type of digital token but more directly tied to the US Dollar due to a claim on central bank money (Exhibit 12). A CBDC may or may not circulate on public blockchains like Ethereum. The main benefit of a CBDC compared to a stablecoin is that the digital token is more directly tied to the economy’s money system (rather than indirectly through safe collateral). However, some policymakers worry a CBDC could result in reduced privacy or introduce other risks. The U.S. House of Representatives also considered anti-CBDC legislation last week; it passed the chamber 219 to 210 with two Democrats voting Yes with the Republican majority.[44]

Exhibit 12: CBDCs have direct access to central bank money

Perhaps the greatest limits to near-term stablecoin adoption come from the underlying blockchain infrastructure itself. Smart contract platforms have come a long way in the 10 years since Ethereum launched, and they successfully orchestrate millions of transactions every day. However, they still have certain weaknesses relevant to payments. For example, there is no privacy by default on most blockchains — every transaction is visible on the public ledger — and users may not want to reveal their historical spending pattern every time they send a payment. To reach stablecoins’ full potential, blockchains will probably need systems that combine verifiable identity with elements of privacy. Some researchers propose embedding this logic directly into the blockchain using zero-knowledge proofs.[45]

Like stablecoins, blockchains are a new technological innovation and are still growing up. As they move beyond adolescence and into full maturity — supported by a more complete regulatory framework — we believe they will bring many consumer benefits and help drive efficiency gains in digital payments and other financial services.

[3] Source: “Stablecoins: The Emerging Market Story”, Castle Island Ventures (Nic Carter, Henry Harris, Wyatt Khosrowshahi, and Charlie Ambrose), Brevan Howard Digital (Peter Johnson and Ross Trachtman), and Artemis (Anthony Yim). September 2024.

[4] According to DeFi Llama data as of July 17, 2025, more than 90% of stablecoin supply outstanding is in USD.

[5] Source: DeFi Llama. Data as of July 14, 2025.

[6] Source: Tether, US Treasury TIC Data. Data as of April 2025.

[7] Stablecoin transactions can be distorted by intra-exchange rebalancing, movement of tokens within the same smart contract, and other factors.

[8] Excluding BSC, which had an unusually large increase in stablecoin transactions in May and June 2025.

[10] Source: Citi Group, Fortune.

[11] Source: Visaonchainanalytics.com. Data as of June 2025.

[12] Alternatively, if both parties to a transaction have an account at the same financial institution (like a large global bank or certain fintech platforms) the transaction can settle in-house.

[13] Source: FSB; figures exclude cross-border wholesale (i.e. interbank) payments.

[14] The FSB reports that the average cost of sending $200 was 6.4% in 2024, and the average cost of sending $500 was 4.3%.

[16] Source: Bank of England.

[17] In the US, the Durbin Amendment in 2010 (part of the Dodd-Frank Act) allowed regulators to cap debit card fees. Another law, the Credit Card Competition Act, was considered as an amendment to the GENIUS Act during Senate deliberations. In the European Union, a 2015 law imposes direct caps on interchange fees.

[18] Source: Edgar, Dunn & Co.

[19] Source: Coinbase, Mercado Bitcoin.

[20] Estimates reflect published on-ramp and off-ramp fees from providers including Transak (e.g. on-ramp, off-ramp), MoonPay, Onramper, and a variety of CEXs.

[21] Citi Group CEO Jane Fraser said in the bank’s earnings call on July 15, 2025 that it was working on on/off-ramp services and other stablecoin-related activity.

[22] Source: BCG Global Payments Report 2024; McKinsey & Company Global Payments Report 2024; Capgemini Research Institute World Report Series 2025: Payments.

[23] These estimates include the payments-related revenue of banks and other diversified financials.

[24] Source: Allium. Data as of June 30, 2025. Calculations by Grayscale Investments.

[25] Source: Calculated by Grayscale Research based on data from Allium on transaction volume by chain and data from Artemis on average transaction costs. Specifically, we assumed 100 million transactions per month at a volume-weighted average fee of $0.40, implying monthly fee revenue of $40 million, and annualized fee revenue of ~$0.5 billion. This amounts to ~20% of total annual smart contract platform fee revenue.

[26] Smart contract platforms earn fees from transaction activity; for background see Ethereum: The OG Smart Contract Blockchain.

[27] Revenue growth could be greater if smart contract platform average fees rise.

[29] Ledger Insights, Cryptoslate, DL News.

[30] Source: DeFi Llama. Data as of July 15, 2025.

[31] iPayments Cards and Mobile.

[34] Mitrade, Mastercard, Visa.

[35] Source: DeFi Llama. Data as of July 15, 2025.

[36] Tether holds a mix of reserves and since ~2020 has been effective at closely maintaining the USDT peg. However, in its earlier history USTD sometimes traded at a meaningful discount to $1.00, partly due to challenges accessing traditional banking services. In 2021, Tether paid a settlement to the US government related to misleading claims about the reserves backing USDT.

[37] Source: Grayscale calculation based on Coin Metrics USD closing price data. Data as of July 15, 2025. Past performance not indicative of future results.

[38] A currency board is a fixed exchange rate arrangement in which the supply of domestic currency is fully backed by a reserve of assets in the reference currency. Examples include the Hong Kong Dollar.

[39] The GENIUS Act includes language directing the Secretary of the Treasury to study “endogenously collateralized stablecoins”, which include digital assets that rely “solely on the value of another digital asset created or maintained by the same originator to maintain the fixed price) (i.e. one stablecoin collateralized by another). The Secretary will then report its findings to the House Financial Services Committee and the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee.

[40] An offshore issuer potentially subject to additional requirements.

[42] Source: Reuters, The Block.

[43] For background on each of these topics see BIS_1, BIS_2, BIS_3, and BIS_4.

[44] Anti-CBDC language will now be added to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). Source: The Hill.

[45] See, for example, “A Note on Privacy and Compliance for Stablecoins”, Darrell Duffie, Odunayo Olowookere, and Andreas Veneris. May 2025.